BY MARCO LIVINGSTONEIn the two decades since he first began his formal education as a painter, Stephen Farthing has worked in a great many rooms and adapted his procedures to the circumstances in which he found himself on each occasion, just as he drew inspiration from his surroundings as a fund of imagery and subject matter.Like many other artists, Farthing has acclimatised himself to each situation. Since September 1985 he has worked in a studio adjoining the small and cluttered office in which he performs his duties as Head of Painting at West Surrey College of Art and Design in Farnham. The studio can be entered from either of two sides: from the corner of his office or from a door opposite which opens on to a long corridor which in turn runs through the partitioned studio spaces used by the students. The possibility of escape thus presented must act in some way as a disincentive to concentration, but the carefully stacked canvases, many of them so large in width that they can barely be turned around in the room, indicate the furious activity which evidently takes place once the administrative chores are at least temporarily out of the way. Getting in after hours or at weekends to work in peace is not always an easy matter, in spite of the helpful attention of the caretaker, since not even senior staff are allowed the responsibility of their own key to the main door of the building. At every possible opportunity, however, Farthing finds his way back into the studio when the rest of the building is quiet. The student working spaces just a few paces away are not unlike the cubicles that he would have used when he was a student at St Martin’s School of Art and later at the Royal College of Art. Elbow room seems always to be at a premium in such institutions, the available light often partly obscured by the ramshackle and paint-splattered screens which shield one’s students working area from another. Each occupant has the choice either of turning a blind eye to the work being created by his neighbour, or of finding a common bond as a spur to further invention. Farthing’s path from student to head of painting in a regional school has taken him through a number of very different working environments. From January to March 1975 he spent a term painting and drawing in a tiny studio in the centre of Paris under the auspices of the Royal College. He cannot fail to have been struck by the contrasts between the spartan but workable room, the lively street-life available just outside its door, and the grandeur and elegance of architectural wonders such as Louvre and the palace at Versailles, where he found himself entranced by Hyacinthe Rigaud’s state portraits of Louis XIV and Louis XV. These were to serve him as the direct models for paintings in which he began to find his own identity as an artist on his return to London in the summer of 1975, works in which he consciously explored the relationship between procedures and stylistic references of the mid-twentieth century and pictorial conventions established centuries earlier. Louis XV Rigaud 1975, his first exhibited canvas and also the first to enter a public collection, was one of a pair in which these concerns were boldly broached.  Louis XV Rigaud  Carceri Awarded an Abbey Major Scholarship on finishing his course at the Royal College, Farthing was based at the British School in Rome from autumn 1976 to summer 1977. The city, with its layers of architectural history jostling against each other, made a deep impression on him. The confrontation of the grandeur of antiquity with the realities of twentieth century urban life mirrored his own situation as a contemporary painter: earlier art directed his ambition and suggested subjects and images, but he wished to synthesize these with a pictorial language and technique clearly of his own time. On his return to England Farthing made his home in a small city, Canterbury, in which modern life likewise revolved around a history still physically present in its architecture. The narrative cycles which he admired in Canterbury Cathedral prompted him to produce his own series of canvases, all in a standard square format, based largely on stories from the Bible. In this group of paintings, titled The Construction of a Monument, he pursued the metaphor with architecture in a particularly down-to-earth way, likening his activity as a painter with that of a mason, bricklayer or sculptor. However grand their frame of reference, however, they were painted in a small bedroom of a conventional late Victorian terraced house. It is not, I don’t think, reading too much into them to suppose that the confined domestic setting in which they were produced dictated the maximum canvas size, while also encouraging Farthing to adopt a range of largely domestic images – including tables and other furniture, boxes and gardening tools – compressed into these restricted areas as deftly as the possessions of the inhabitants were stored and arranged in the rooms in which they lived.

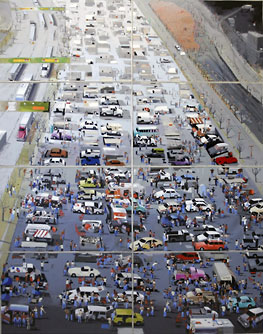

Flat Fish  Mrs G’s Chair From Easter to September 1982, while still living in Canterbury, Farthing rented a spacious studio on the seafront at Whitstable and there began painting large-scale domestic interiors from drawings that he had begun the previous Christmas. The horizontal format of these canvases, which had their source in the novels of Balzac, suggested that they were like mirror images of actual rooms. They were much more than illustrations to literary texts, for his interpretations were fleshed out by his own experiences, memories and imagination. The daily journey from home to studio was, one might say, played out in reverse once he entered his working environment, for there he made it his task to summon up a domestic setting to replace the one he had left behind, linking his art directly to the circumstances of his life and routine. The silvery light which fills these canvases, moreover, not only constitutes a faithful rendering of Balzac’s description of the austere house of the Grandet family, but seems also to be a response to the natural setting in which Farthing was making these paintings, to the characteristic reflections of cloud over the grey water of the English Channel. Farthing continued painting interiors when he moved house from Canterbury to Nonington, Kent in September 1982, setting up his studio on the upper floor. The outstanding features of the house – its great character, its age and solidity, its unexpected corners, the light and colour streaming through the French windows from the expansive garden – all altered the conception of his paintings. Although the details of the interiors he was painting had their origins in Balzac, the framework of the pictures was based on the house itself, in particular on the cellar and roof spaces in which he had done some building work on moving in. Towards the end of his stay in Nonington, he set himself the challenge of summing up in pictorial form his own experience of the landscape of that part of the world in his Town and Country series of 1985, reflecting not only the coexistence of farming and industry – there were coal mines just down the road from his village – but also exploring the takeover of rural tranquillity by the urban habits of the Porsche-driving commuters whom he had as neighbours. In this series more than in any other, Farthing set himself the challenge of representing the environment in which he lived and worked. Having commemorated his departure from Nonington, Farthing moved in September 1985 to Farnham, Surrey, to take up his new teaching and administrative duties. The complexity both of his immediate working conditions and of the area in general have already left their mark. Farnham to outsiders may sound like a quiet rural retreat, and indeed it remains a town of considerable charm surrounded by pleasant countryside, but it is also only a few minutes’ drive from the Ministry of Defence installations at Aldershot. In Farthing’s new paintings the Englishman’s fantasy of country life as timeless, peaceful and pure has been irrevocably invaded by fighter planes and tanks, computers and other products of the latest technology. The sense of claustrophobia and overcrowding which mark these pictures may also have subconscious origins in the frenzied turn which the artist’s own life has taken with the new responsibility of a young daughter and the many and constant demands of his job. It would be misguided at this stage to pry too much into these possible factors. Suffice it to say that Farthing continues, as he has always done, to respond to the places and conditions in which he makes his paintings. Farthing is best-known to a London audience as a painter of interiors, but these form only an interlude in his development since finishing his studies at the Royal College of Art in the mid 1970s. It is only through historical accident that those particular pictures received the most attention, thanks to the fact that they were exhibited first at the Paris Biennale in 1982, later that year at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford and then at his first one-man show at the Edward Totah Gallery. The fact remains, however, that Farthing has been consistently sensitive to architecture and in a wider sense to his surroundings as factors influencing his choice of subject-matter, imagery, technique and approach. His experience of each place in which he has worked has often been relayed in terms of the art which seemed in some way to define that culture. Recognizing that no artist works in a vacuum, as early as Louis XV Rigaud 1975 he chose openly to declare his sources so as to share with the spectator the tradition and frame of reference within which his own pictures were conceived. The model served not only as a useful starting-point and as a measure of the historical distance between the means used by artists of different periods, but as a way of releasing himself from the pressures of originality for its own sake. It is immaterial whether the spectator knows the particular painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud on which Farthing’s Louis XV Rigaud is based. What is at issue is the entire genre of official state portraiture with its pomp and pageantry, its shorthand symbols of wealth and power, its glittering surfaces and ostentatious display. In such circumstances one of the least important points is the extent to which the artist has achieved a convincing likeness, a question which clearly struck Farthing when he noticed how indistinguishable was Rigaud’s treatment of Louis XIV in the Louvre and that of his seven-year-old son in the portrait housed at the Muse de Versailles. In Farthing’s painting, the sitter’s face is barely sketched in, a kind of flat cartoon-Cubist figure swallowed up by the clothes and possessions which define his royalty and wealth. The attributes which defined him in the original painting have been translated into twentieth century terms: the carpet is conveyed in a technique borrowed from Jackson Pollock, the drapery hanging in the background is like a fragment of stained colour from a painting by Morris Louis, there are bold decorative patterns as in Matisse and fragments both of collage and masking tape, among the most favoured of modern innovations. Analysing the intentions at work in Louis XV Rigaud, Farthing recalled in 1979 that ‘perhaps the thing that prompted me to paint this particular picture was an interest in packaging’. In other works of the same year, such as Flat Hat and Flat Pack (coll. Royal College of Art, London), the source of this concern in Pop Art was more immediately evident. In 1973 he had produced stylized paintings such as Piano Box and Harpsichord Box, in which single objects were pinned flat to the bare canvas with recourse to traditional techniques such as wood graining, marbling, gilding and lacquer work, all of which he had studied in a trip to Italy in 1972 and at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Drawn less to the art of his own time than to the work of earlier painters and craftsmen, it was almost through an act of will that he found in Pop sufficient stimulus to broach contemporary subjects and techniques in his own work. Following the example of Robert Rauschenberg he experimented with photo-silkscreen in his paintings, responding also to Jim Dine’s suggestive treatment of objects in a one-man show which took place while he was living in Paris. ‘Most of my imagery’, the artist later recalled, ‘was a household kind of imagery, cigarette packets, objects around the kitchen and things like that. In some ways I was more interested in the process – printing, adjusting – than I was in the imagery, which seemed to me a vehicle’. Farthing’s estimation is borne out by his adaptation of the principles of Cubist collage and by the references to a variety of disparate styles, adapted and recycled as dispassionately as in the work of any Pop artist. His apparent neutrality towards the styles that he was employing seems, however, to have sprung not from an impulse to be modern but, on the contrary, from his devotion to more traditional forms of painting. An artist who as late as the autumn of 1972 could paint a large figure picture on the theme of The Blind Leading the Blind, inspired by the Peter Brueghel painting which he had seen that summer in the museum at Naples, was unlikely to give himself unconditionally to any self-consciously ‘modern’ style. His own attitude towards the insertion of contrasting passages, moreover, was formed by his own perceptions of Old Master paintings. He was particularly fond of two paintings by Vermeer in the National Gallery, London – A Young Woman seated at a Virginal and A Young Woman standing at a Virginal – in which there is a sophisticated play on the idea of a picture within a picture. In the latter there is an implicit reversal of one’s expectations in that the painting on the virginal and the framed landscape on the wall are each like views through a window, whereas through the window itself nothing can be seen apart from the blinding white light. What painter could fail but be moved by this expression of faith in the power of the medium to transform illusion into reality by means of the imagination? As a student it may be that Farthing loved the great art of the past too much to be able to give himself to the conventions of his own time. The relatively low ambition then ascribed to those who still wished to devote themselves to a representational art seems to have done nothing but confirm his will to find his own way out of the history of painting. ‘Looking back on it, it surprises me that I wasn’t revelling in contemporary painting. For some rather strange reason it didn’t seem to interest me that much, and I never felt an obligation to it. Looking at a lot of contemporary art seems to me like work, whereas looking at the history of painting is pleasure’.

Seen As Farthing’s interest in packaging, allied to his devotion to traditional forms of painting, found the perfect marriage during his stay in Rome from 1976-77. It struck him that the architectural and decorative settings which housed the great Renaissance frescoes such as Raphael’s Stanze and Michaelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel were themselves a form of packaging, a context for the pictures they contained. Accustomed as most of us are to seeing art in reproduction, the experience afforded by the unity of the paintings with their architectural setting fudamentally changed his perspective: ‘One of the things that excited me about the paintings in Rome was that they were situated on a wall for most of the time and they were painted either directly on the wall or incorporated into the church’s architecture in such a way that they weren’t easily taken out and put into a gallery. Most of the painting and sculpture that I saw in Rome and Florence was seen in situ, in a particular chapel in a particular church, and the thing that perhaps was most exciting about actually seeing these paintings was the fact that one didn’t only see the painting, but also the trappings around them You’re not just looking at a painting but [at] a painting in a situation’.  The Falls at Fiedo  The Whitney Wedge  The Whitney Affair The architectural detailing that captured Farthing’s imagination in Rome had the function not only of framing the images but of embelleshing the structure so as to make it appear more luxurious. Even details such as egg and dart mouldings were to him potential pictures in themselves as well as what he called ‘creators of wealth’. Such motifs were taken by him as the subject matter for one of the first canvases which he made on his return to England in 1977, Sistina, where they were elevated from their customary supporting role to centre stage. In the year that followed, Farthing devoted himself exclusively to paintings of Italian architecture based on the observations he had amassed during his stay in Rome. In canvases such as Villa Madama he created a new context for particular details that had given him pleasure, in this case ‘rehanging’ the curtain, its opulent folds still intact, that had so convincingly added to the sense of luxury in the Sistine Chapel. The spatial inconsistencies that lead the eye from a flat surface to an illusion of cavernous depth are deliberate, encouraging the kind of physical disorientation that one may experience when studying this kind of awesome interior space at first-hand. The conflicting viewpoints of Cubism are given form here not so much to describe the contours and corporeality of an object but to encourage an identification of the painting with the architectural structure depicted on its surface. Farthing was not content with producing pictures of architecture. The canvases in some way had to become physical equivalents to the structures they depicted. To this end he began making his own paints out of an acrylic medium mixed with dry pigments, working them up to a colour and consistency that convincingly mimicked the appearance of stone or, in later works, crumbling plaster. The tactility of the support is likewise exaggerated: areas of rough canvas are left bare, and the surface is often built up with further patches of canvas, an elaboration of the techniques of Cubist collage. In works such as Carceri different levels of time are exposed through imagery and technique alike. In the most mundane sense, the viewer is presented with the stages in the making of the picture, layer over layer, but this material evidence is extended metaphorically in the confrontation between the rubble of ancient Roman architecture and a later fresco painting which itself seems to consist of one surface over another. The title pays tribute to the Piranesi etchings which supplied a useful intermediary between the architecture of Rome and Farthing’s paintings, and alludes to the fact that the figures are literally imprisoned within the canvas, frozen in time and locked into a constricted space. The whole of Rome, Farthing recognized, was like a museum. Confronted with the weight of history, a young painter could try to sweep it all away, as the Futurists had attempted to do. Or, on the other hand, he could accept the situation and use the material surrounding him to build something of his own. Farthing chose the second option. Daunted but excited by the prospect of representing the collision of old with new that seemed to him the salient feature of the city, he was prompted to find ways of creating a homogeneous idiom out of disparate parts, a wholly modern painting out of the fragments of past art and architecture. The practice he had already established of quoting from other art was one that he found especially useful in this respect. ‘For those interested in sources’, he wrote when he first exhibited these canvases in 1979, ‘I should mention that nothing in these pictures comes from my fantasy. Everything in them can be traced back to historically real sources, though I’ve taken great delight in juxtaposing vastly different periods; like the archaeologist chipping away at 20th century brick reveals a 16th century fresco on a 12th century church wall’. His words and practice reveal a rare humility about his place in the history of art, one in which ambition is securely anchored to tradition. Canvases such as Flat Fish, Fish Dish and Plaice on a Plate which followed immediately on from the paintings of Italian architecture seem at first sight to represent an astonishing shift in both subject matter and tone. In the years that I have been following Farthing’s development I have since come to accept such surprises as a matter of course. Cheerfully oblivious of our expectations or of the time that it takes us to come to terms with the work he has just produced, he responds spontaneously – and, one later realizes, with unquestionable logic – to his changing enthusiasms. The fish paintings, for example, have links with earlier pictures such as Louis XV Rigaud in their unabashed decorativeness, sense of humour and animation. With the benefit of hindsight one also recognizes the continuity of purpose from the architectural paintings, particularly in the examination which each group undertakes of the relationship of the painted image to the decorative framework in which it is viewed. The fish pictures, in fact, also had their origins in the year spent in Italy and in ancient art: the spritely animal paintings which he saw in the interior of an Etruscan tomb prompted him to try such subject matter himself.7 As he was not a pet-owner and did not have easy access to a zoo, the easy solution seemed to him to draw and paint fish purchased from the local shop; as he pointed out, they were so recently deceased that they seemed still to have a gleam in their eye, so they were the next best thing to a live animal subject. He made fifty or sixty charcoal drawings on the subject before trying them out on canvas in wax encaustic. The thought process which united these paintings with the architectural series preceding them was succinctly stated by Farthing in the leaflet accompanying the first exhibition in which they were shown together: ‘Why put fish and architecture together in an exhibition of paintings? Well, the unifying factor is not so much the subject matter as the treatment. Look at one of the fish paintings. There’s a flat fish in the middle painted to recall a real dead fish, around it swim other fish, abstractions if you like, though with more ‘life’ in them than just decorations on a plate. What we’re looking at is at least three levels of unreality. ‘As soon as a three dimensional fish is painted, however true to life it looks, it is no longer real. The decorative fish are perhaps even less real – though they do exist in a Mycean wall painting and they are alive! So there’s a picture of fish on pictures of fish painted on a plate – a painting within a painting within a painting. And this goes for the architectural paintings too – a picture on a wall of a picture on a wall. One constant from the Rigaud portraits through the architecture paintings to the fish studies was Farthing’s preference for a vertical format, roughly the average height of an Englishman and slightly less than the span of his arms in width. Other features common to his early work were the use of strongly-delineated forms, a frank decorativeness and the insertion of at least one or two passages in strong colours. None of these characteristics, however, are in evidence in his next series of paintings, The Construction of a Monument. Sombre and painted in earth colours and stony greys, they rely largely on tonal contrasts and emphasize modelling and the illusion of volume rather than surface design. In some cases the edges of forms are picked out in a heavy black line indebted to the work of Fernand Lger, but in others images seem to float in and out of focus thanks to a deliberate softness of contour. The combination of a square format with compositions based either on a central image or on a circular activity around a central void give them a sense of centrifugal motion, freeing them from the conventional gravity of the previous images. Finally the sense common to the previous work of an image pinned to the surface – whether it be a portrait, a still-life or a fragment of a building – has given way to an emphasis on narrative, not in order to relate a particular story but for the sheer sake of introducing the movement implicit to a sequence of events. On witnessing such wholesale changes in form and style, one might be excused from thinking that the new series constituted a repudiation of the work that had come before. The reverse is in fact the case: having examined one set of conditions, Farthing was curious to explore other conventions. The devices and attributes, different though they may seem, are all drawn from a common fund and all remain at the service of an analytical redefinition of what constitutes a painting. Certain factors, moreover, carry on as before, notably the emphasis on tactility, on the materiality of paint, and on a vocabulary of familiar images that could be described as the equivalent to everyday speech. Above all the metaphor with architecture is not only maintained but extended in the very choice of subject. As the artist succinctly explained in the statement accompanying their exhibition as a group in 1981, ‘They dramatise the range of work involved in such a project: the constructional, the decorative, the symbolic and the mystical’. In the Monument pictures Farthing likens his activity as a painter to that of a sculptor or an architect, shaping his forms in such a way as to give them a convincing three-dimensional presence. Indeed, the standard image of the small painted studies leading to the series proper is that of a plasterer’s trowel, a tool very much like the palette knife that Farthing actually used to drag the paint across the surface. Just as expressionist painting was coming back into fashion, proposing a veneration of the brushstroke as the authentic mark of the artist’s personality, Farthing was seeking to demystify painting by identifying it with procedures and activities common to most people’s lives. His respect for his chosen medium and profession is undoubted, but it goes hand in hand with an equal respect for the creative acts, however mundane, of which all of us are capable. Among Farthing’s monuments are memorials not only to such luminaries as a baron and a king, but also to those who celebrate and propagate life – a musician, a gardener, a ploughman – and even to those, like the miser, whose actions in some way deny it. The Monument to a Miser, a particularly austere canvas depicting empty coffers, hints at the fact that Farthing’s first plan for a narrative series had been to illustrate Balzac, who had created in the character of Monsieur Grandet the very personification of avarice. It was to be another two years before Farthing decided to tackle this literary project. His first suspicion was that the subject should be a more generally recognizable one, so he looked instead to the Bible, choosing well-known subjects such as the construction of the ark, the wedding at Cana and the expulsion of the money-lenders from the temple. No. 5 John 2 v 16 depicts the tumultuous moment at which the tables of the money-lenders were overturned by Christ. Farthing was intrigued and amused by the challenge of relating violent activity by means of a still image, a paradox which matched that of the popularity of the subject itself: the money-lenders may have been expelled from the temple, yet on the walls of innumerable churches they stubbornly held their place, cash still in hand. In Farthing’s version the culprits themselves have disappeared, but their coins remain forever suspended in mid-air and their furniture condemned to being overturned without ever falling over. By means of inconsistent viewpoints, of elements painted sideways or upside-down, and of a composition that appears to whirl around a central vortex, Farthing dislocates our sense of gravity and subjects us to the violence and disorientation which are the essence of the subject. From the first Biblical subjects Farthing turned his attention to the Monuments which ultimately dominated the series. In these the narrative element is not a given story but the dramatization of the process itself by which each is constructed. In Monument to a Musician, for instance, it is almost as though one were being presented with an isometric diagram illustrating the way in which the three-dimensional blocks would be fitted together, complete with the linking pegs. The corporeality of the boxes and decorative cartouche alike in Monument to a Propagator is so emphatically conveyed as to persuade us of the existence of these objects as real things. Stone surfaces are made to look stony, and walls are remade with a thick-textured paint applied with a palette knife as if an actual wall were being replastered with a trowel. Farthing spoke at the time of his delight in the play ‘between very possible sculptural qualities – possible in terms of being made – and highly improbable qualities that would never allow it to be made’. He wanted to banish the pretence that he felt was the basis of naturalism – the presentation of a scene as if it were a view through a window – while making his images credible as material equivalents to reality. It seemed necessary to him, in order to achieve such an ambition, not only to make his own paints but to devise appropriate means of applying them to the canvas so that he and the viewer alike could conceive of the process of representation not as making art but as making an object. ‘I’m building them, I’m not painting illusions of them’, he explained while he was still working on the series. ‘They are monuments. Of course they’re illusions of monuments ultimately, but my thinking about them whilst I’m painting them is that I’m constructing this painting. I’m not painting an illusion of something that exists somewhere else’. Farthing’s conviction that he was ‘building’ his monuments in paint, and his choice of subjects such as Noah’s Ark (No. 3 Genesis 6) and A Pantheon, clearly indicate the extent to which his architectural concerns continued unabated. For several years he had been involved with project work in the School of Architecture at Canterbury School of Art, so he could not help but see the connection between the activity of a painter and that of a designer of buildings. An additional impetus seems to have been his admiration for the retrospective exhibition of paintings by Patrick Caulfield held at the Tate Gallery, London, at the end of 1981. A major part of Caulfield’s exhibition had been devoted to the series of large canvases initiated in 1969 representing slightly out-of-date domestic, restaurant or office interiors on a one-to-one scale; given the almost total absence in these pictures of human figures, we as spectators have the sensation of becoming the protagonists, as if each of these empty environments were only waiting for our arrival to be jolted out of its state of languorous reverie. On his move to a more spacious studio at Whitstable in 1982, Farthing set to work on a group of large-scale interiors based on the writings of Balzac which he had rejected as a subject only two years earlier. As had long been his practice, he rehearsed his ideas for the paintings in a series of charcoal drawings, including in this instance both compositional studies and sketches of particular pieces of historical furniture from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. The paintings that resulted, titled as a group The Museum at Night, were first shown at the Paris Biennale in the autumn of 1982. Their subject matter and formal characteristics initially appeared to make them another shocking about-face. Just as one had become accustomed to the ‘sculptural’ preoccupations of the Monuments, Farthing shifted his attention to interior spaces. The square format had given way again to the rectangle, this time arranged horizontally; the palette was lighter in tone and the concentration on mass had been exchanged for an atmospheric treatment of space. As in previous instances, however, the Museum at Night series, if viewed more calmly, does in fact develop previous concerns with rigorous logic. The most obvious evidence of this continuity is the obsession with architecture, for so long a sub-text in his paintings, which finally emerges here as the overt subject matter. The concern he had long shown with making paintings that were like objects has been redirected to actual objects, specifically to 18th and 19th century furniture, the decorative arts equivalent to the portraits by Rigaud that had served as the models for some of his earliest work. Gone are the opaque earth colours of the Monuments, replaced by translucent and pearly greys, but the paintings remain defined largely by a single colour and by tonal variations of extreme subtlety. Farthing’s personal exploration of Cubism is given another twist, this time not simply in the treatment of a single object but in the manner in which he describes the entire volume of a room, imagining the walls and sometimes even the floors to be transparent surfaces so as to place the spectator at once inside and outside the space. In the Monuments human presence was implicit through the constant reminders of the artist’s activity as a fabricator of objects and of persuasive fictions. In the Museum at Night it is through the objects and settings that people are called to mind. Not only are chairs designed for the human body, they are also, as Farthing insists by a sensuous and often erotic exaggeration of their contours, convincing substitutes for people. When several pieces of furniture are brought together in a stage-like but clearly domestic space, their role as reminders of human confrontations in daily dramas is inescapable. For all their humour and come-hither seductiveness, these canvases also have a claustrophobic, enclosed quality in which we as spectators are entirely implicated. The ingredients of this theatre of home life could be said to be, in equal parts, Vuillard’s intimism, Caulfield’s contemplative inwardness, and the suffocating passions and possessiveness of Ibsen or Ingmar Bergman. Just as he was setting to work on the new series, Farthing described the change of format as ‘more like writing than stacking bricks’. It was an apposite metaphor, given that the source of his imagery was an explicitly literary one. One passage from Balzac’s novel Eugnie Grandet, describing the main room of that ‘grey, cold, silent house’ in which the old miser lived, is particularly pertinent to paintings such as Mrs. G’s Chair and M. Grandet’s Principal Room, identifying the wealth of imagery and going some way towards explaining their austere colour and restricted emotion: ‘The principal room on the ground floor of the house was a parlour, which was entered by a door under the arch of the gateway. Few people know how important a part this room plays in the life of the small towns in Anjou, Touraine, and Berri. The parlour is hall, drawing-room, study, boudoir, and dining-room, all in one; it is the theatre of family life, the centre of the home The two windows of the room, which had a floor of wooden boards, gave on to the street. Wooden panelling, topped with antique moulding and painted grey, lined the walls from floor to ceiling. The naked beams of the ceiling were also painted grey, and the spaces between showed yellowing plaster… An old brass clock case, inlaid with arabesques in tortoise-shell, adorned the clumsily-carved, white stone chimney-piece, above which stood a mirror of greenish glass, whose edges, bevelled to show its thickness, reflected a thin streak of light along another antiquated mirror of Damascus steel. In the window nearest to the door stood a straw-bottomed chair, raised on blocks of wood so that Madame Grandet as she sat could look out at passers-by in the street’. Farthing’s intention, however, was not to illustrate a section of a novel but to use the literary description as a conveniently detailed spur to his own visual imagination, just as he had earlier used other paintings as models for his own. Balzac, like other French naturalist writers of the 19th century, lent an air of objective reporting to his tales of human interaction by supplying lengthy catalogues of the attributes and possessions of his protagonists. The similarity of such descriptions to stage directions helped to induce the distinctly theatrical air of these paintings and the ones that followed. The room is treated as a world in itself; nothing can be seen through the window for the simple reason that, like the room as a whole, it is an abstraction, a figment of our collective imagination. Farthing was particularly intrigued by the way in which Balzac’s comments took no note of the fourth, unseen, wall, as if accepting that the room he was describing was no more than a stage for the human drama being enacted. This sense of the wall as a transparent surface opened up immense pictorial possibilities in dealing with an architectural space that was not just described but could be experienced by the spectator as an almost physical substance. Particular passages in works by Balzac and Flaubert can be wedded to some of the canvases that followed, an instructive exercise not for ‘explaining’ the painting but for retracing the decisions made by the painter in interpreting the descriptive material thus supplied to him. Other interiors were not specifically rooted in these texts: for example, The School at Rome was a memory picture of the library in which he had spent one of his student years nearly a decade earlier, while in The Nightwatch he cheekily appropriated Rembrandt’s title to portray a security guard’s gloomy room after hours, apparently illuminated only by the cool light of a television screen. Even in these pictures, however, some of the devices seem also to have been prompted by his reading, particularly by Balzac’s suggestions of the ways in which adjoining rooms can be reconstituted in the mind through sound. Such noises can not only make walls ‘invisible’, they can also help one to imagine the appearance of the room above, as Farthing has done in substituting creaking floor-boards with a transparent plane in perspective. The extraordinary productivity and inventiveness with which Farthing gave himself to the theme of interiors from 1982 through to 1984 are vivid proof of the wealth of possibilities offered to him by the subject. The pictures contain innumerable signs of human activity, enlivening them with an emotional intimacy and drama. Farthing’s evident pleasure in inventing one bustling space after another led him to inject ever more spirit into his descriptive line and imagery, in the process encouraging him also to key up the colour to an unaccustomed brilliance and richness. Another factor in the growing ebullience of his paintings of rooms may well have been a friendly rivalry with Graham Crowley, a painter of his own generation who in 1982 had initiated his own series of domestic interiors populated by alarmingly animated objects. A sense of humour had surfaced in Farthing’s earlier works, notably in Louis XV Rigaud and the fish pictures, but never had it been so broad as in Out of the In Basket, Index Svres or Word and Shelf. Prized objects such as sumptuously decorative ceramics are here inflated to grotesque proportions: a cautionary tale, it would seem, on the way in which possessions can begin to take us over if we give them too much importance. The evident pleasure which Farthing had in making these paintings is infectious, thanks particularly to the wit of the technical resources summoned to the service of his representational devices. Within each picture there is a heady mixture of pictorial conventions: ‘low art’ forms such as comic books, the decorative arts of furniture and ceramics, hints of book illustration and genre painting, and even techniques such as gold-leaf all jostle for attention in scenes of such exuberance as to verge on the explosive. Nowhere is Farthing’s delight in manipulating paint more evident, but his love of the medium does not prevent him from treating it playfully and without the solemnity so often deemed necessary in a ‘serious’ painter. He clearly has not forgotten the days, not so long ago, when every painter felt under pressure to ‘respect the integrity of the picture plane’, but what the hell? Now that artists had begun to free themselves again of such constrictions, why not hurl the audience into a deep plunging space? He remains secure in the knowledge that the patches of paint, applied in an almost carefree way with a palette knife, will bring us back to reality. The rectangles of gold leaf which function as the door hinges in Another Simple Heart literally anchor the image to the surface. Anything is possible so long as every convention is revealed for what it is. Farthing has consistently and openly avowed the fictions involved in representing the visible world on the surface of a canvas or sheet of paper, relishing illusion only to undermine it, like a rare kind of magician who lets you in on his tricks just as he performs his most spectacular sleight-of-hand. In his work of the mid-1970s the illusions had been largely on the surface: a sense of ostentatious richness was projected through the aura of luxury offered by the materials themselves (e.g. gold paint), pattern, and ready-made symbols borrowed from much earlier art. Since then Farthing’s illusionism has been applied not just to the devices of painting but to the depiction of objects, which in the Monument paintings and interiors have been reconstituted with such obsessive intensity as to make him appear almost a sculptor manqu. As if to counter this impression, however, he has brought into play another battery of (anti)illusionistic devices proper to painting, many of these allied to Cubist ruses for representing three-dimensional form while simultaneously testifying to the methods by which this sensation of reality has been achieved. Divergent perspectives and an expressive distortion and fragmentation of objects in the end, however, form part not of a Cubist revival but of Farthing’s insatiable curiosity about the look of things. It is as if he were pulling apart not only each individual object in order to examine it more closely, but was doing the same with the interior space as a whole, reconstructing it from memory and from his imagination.  The Modern Affair  Browns Town By the end of 1984, Farthing felt he had come to the end of the interior theme, at least for the time being, and was ready for the challenge of another abrupt change of subject and form. As a prelude to the Town and Country landscapes, in which he bid farewell to rural Kent in the summer of 1985, he experimented briefly with a series of still-lifes in which home computers were piled together, sometimes around the faade of an early Renaissance church such as San Miniato al Monte in Florence, to form a metaphorical cityscape. Fairly small in format – 107 x 124 cm – canvases such as Stew Pond and A Winter’s Tale were in a sense a holding operation, a relaxing interlude in which the artist played with combinations of images within an idiom of bold draftsmanship and sometimes acid colour essentially taken from the last of his interiors. The injection of a jarring contemporary note in the form of new technology – a feature which had entered his art as early as 1982 – at this stage may have appeared to be simply a novelty, but it was soon to emerge as a major theme. Before embarking on his speculations on the urbanization of the countryside, however, Farthing reflected on the ideas which had preoccupied him ten years earlier in Louis XV Rigaud in his first figure paintings since that time. These three pictures, each titled L’Emmerdeuse, were variations on another eighteenth-century source: a portrait of Madame de Pompadour by Franois-Hubert Drouais in the National Gallery, London. As with the Rigaud, the figure is defined not by her face – which is determinedly excluded from the canvas – but by the attributes of her luxuriantly-patterned clothing and by the activity in which she is so engrossed that her body seems to have been joined with the furniture as a kind of strange hybrid object, half-human, half-inanimate. Farthing’s preoccupation with the history and conventions of painting – in its intellectual dimension and more prosaically in its techniques and in the practicalities of picture-making – has been such a consuming passion that the personal references in his art have often been relegated to the background. Each group of canvases, however, has been specifically and consciously rooted in his experiences of a particular place. Nowhere is this more evident that in the Town and Country series, in which he parts ways not only with the idyllic circumstances of his life in a quiet Kent village but also with one of the most popular and persistent genres in English painting: the unspoiled rural landscape. The collective dream of the countryside which survives in our highly urbanized society exists, Farthing implies, only in our imaginations and by extension in the art forms which we continue to employ to describe it. It is not just industrial waste and random litter which has blighted the scenery; the social and economic forces which have extended commuter life further and further from the city have also taken their toll. Thus it is that in canvases such as Traditional Cover, Coppice, and National Trust the initial impression of a timeless pastoral scene or of a protective wooded enclosure soon breaks down under the evidence of mountains of discarded cartridges, noisy tractors and flashy sports cars. England as an agricultural society is now nothing but a myth; for farming to survive at all as an economic activity, it has long since had to trade the picturesque virtues of a direct confrontation of man and animal with nature for the reality of a highly mechanized farming industry. The deromanticization of landscape painting effected by Farthing in Town and Country has continued unabated in the complex, intricate and even lurid paintings on which he has been occupied since his move to West Surrey in the autumn of 1985. Scenes of almost nightmarish congestion such as Brother, which the artist succinctly described as ‘A Soft Room and hard-ware’23, hint not only at the crushing pressures of modern life but at the reigning political climate of rivalry, suspicion and the double-bluff of military power games. The scene of action is a conflation of Colonel Gaddafy’s desert tent, the centre of his operations against western superpowers, and the Ministry of Defence installations at Aldershot, only a stone’s throw from the artist’s home. What is one to make of the proud displays of the latest machinery? Are these to be celebrated as the advances of science and of our capacity for invention, or feared as the instruments which may shortly bring about our own destruction? Farthing’s prominent use on one canvas of an image popular as a perceptual game – a rabbit’s head doubling as a long-billed duck – suggests, however poignant or alarming the joke may seem, that we can look at the situation either way. So this is where Stephen Farthing has brought us in just over a decade, from 18th century state portraiture and Roman architecture to the brink of nuclear disaster in 1987. Two thousand years of history neatly tracing, as if by chance, the rise and fall of the West. Yet the changing fortunes of empires and political systems are only marginally of concern to him. The one continuous thread, the only system in which this unconventional painter has maintained an unwavering faith, is that of the conventions of his chosen medium, constantly renewed and revitalized. Marco Livingstone London, June 1987

Reproduced by kind permission of the author, the Edward Totah Gallery London and the Museum of Modern Art Oxford © 1995. © Marco Livingstone 1987. |